When Pity Becomes a Marketing Strategy

What Paul Castle’s Videos Reveal About Authorship and Branding

Scrolling through social media this week I came across another video by Paul Castle. You might know him. He’s a children’s book author with over 3 million followers on TikTok. His videos often feature playful pranks with his partner, snapshots of life living with blindness and sweet moments with their service dog. They’re a charming couple, and his books (brightly illustrated, self-affirming titles) fit perfectly into his brand.

On this video, I paused. He was crying.

That, of course, was the point.

He sat in front of a wall of his own books, visibly upset, saying, “The book deal didn’t go through.” My first instinct, as writer myself, was to empathize. To support. To boost a marginalized voice in the publishing world. But then I paused again, because “haven’t I seen them do this before?”

Yes. In fact, I’ve seen it several times.

It’s a pattern in sales spaces known as pity marketing.

In the video, between tears, Castle stated a bookstore chain required him to change the title of his book if he wanted them to sell it. He did, but then the bookstore still didn’t take the deal, leaving them with a wall of books. The implication being, “we’ve been wronged, please help us get rid of this stock by buying a book on the TikTok shop (the apps native built in store).”

And it worked. Tons of commenters rushed to share, “just bought one for my grand babies!” and similar comments.

But many others challenged what Castle said, because that’s not how bookstores work. A bookstore would not ask an author to change their title and they’d be very unlikely to order directly from the author. Like… VERY UNLIKELY. This is a battle indie authors deal with all the time.

But as it turns out, Castle wasn’t just speaking as an indie author, he was speaking as a publisher.

So when he was upset in his video about “the book deal not going through” his audience naturally thought he'd being slighted as a gay author, but the reality is the bookstore chain cannot work with them because, as a PUBLISHER, Castle is not in the system the bookstore orders from. (Castle’s micro press, Paul Castle Studio represents his three titles, doesn’t currently meet the criteria for being included in the Ingram Content Group distribution service.) This kind of stuff happens all the time. It’s not a slight, but rather, everyday business. He’s not a struggling indie author, he’s a too-small publisher. That’s a detail a lot of viewers won’t realize and it changes the dynamic.

Imagine if Scholastic made a TikTok crying that The Hunger Games didn’t get picked up by a retail chain. Or if Anchor Books wept publicly over The Handmaid’s Tale not being stocked at Barnes & Noble. It would be bizarre. We would think that strange.

But when Castle tells that story as the face of the brand, as the author, the press, and the poster child for representation, people don’t know all the details. They see a queer, disabled man trying to share his story and being turned away. And they want to help. They want to support. They want to buy the book.

And that’s exactly the point.

Now, don’t get me wrong, marginalized authors do face incredible barriers to distribution. Disabled, queer, and BIPOC creators are routinely undercut, underfunded, and devalued by traditional gatekeepers. That’s real and it matters.

But we also need to talk about how visibility and identity can be weaponized in marketing, especially when the story being sold is selective, or misleading. Castle’s content walks that tightrope that I don’t like, that could be damaging to other queer or disabled people who are actually facing discrimination in the publishing industry each and every day.

(I’ll be writing an, intentionally separate, article about this topic soon.)

When someone controls both the narrative and the product, it gets murky. Especially when the tears don’t always match the facts.

Readers want to support authors. They want to support good causes. But they also deserve transparency— especially when their sympathy is being used to move units.

SO if Paul’s video is really about being upset about not getting into a bookstore, about not getting into Ingram, why the wall of books? Well in the first video Castle claimed, “if we delayed ordering the quantity that the bookstore wanted, we might have missed the opportunity entirely”. Then in the next video Castle said, “the bookstore chain never ordered those books. I never said that they ordered those books.” Then goes on to explain the boxes were for their personal stock (likely for TikTok sales).

…Remember what I said earlier about making a video to garner pity? So you’d feel bad and buy a book from their TikTok shop?

His contradiction outs his attempt at pity marketing. Its was a messy, calculated, strategic marketing move. One that’s worked for them before.

Bookstore Botherer

I want to come back to a point I mentioned earlier about having seen this from Castle before. This isn’t the first time Paul Castle has used emotional storytelling to rally support and it’s caused controversy. In fact, almost exactly a year ago, in June 2024, he went viral with a similar video.

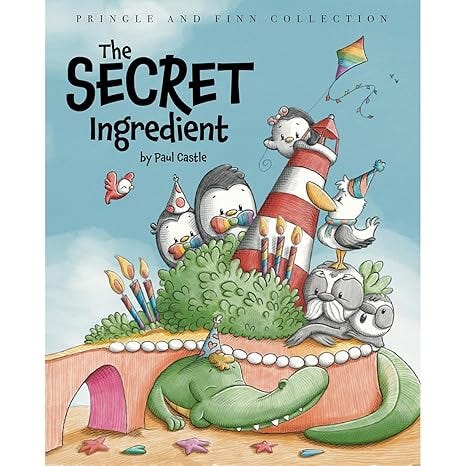

That time, he posted a tearful video claiming a bookstore had “banned” his picture book, The Secret Ingredient, after returning 100 copies and canceling a signing event. On camera, he said the store’s decision was because of the book’s queer content, that “he couldn’t think of any other reason they wouldn’t stock it”, prompting immediate outrage. His followers flooded the comments with support and then, flooded the bookstore with harassment.

Castle included the name of the employee he spoke with (Tanya), which led to a wave of attacks against multiple bookstore staff with that name. In fact several Tanyas across the country (completely unrelated to the incident) were hunted down and flooded with threats. Tanya’s bookstore was overwhelmed with negative reviews and messages. And it turns out, the situation may not have been quite what it seemed.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Industry professionals were quick to point out that no bookstore places an order for 100 self-published books without working through a distributor (now we know Castle is the distributor, but a store still wouldn’t order that many copies, not even for a signing or a launch). According to later reports, the original staff member who placed the order had left, and the store simply chose not to move forward with stocking the book. A disappointing, maybe even careless decision, but not a ban. Not censorship. And certainly not deserving of online harassment crusades that Castle’s following gladly partook in, and which Castle did nothing to quell.

Once again, Castle benefited from the backlash. His book sold out. Dozens of indie bookstores offered to carry it in solidarity.

But what started as a tearful plea for justice became a campaign that hurt real people—people without the same platform, reach, or safety net.

And now, here we are again. June 2025. Another video. Another vague story about rejection and mistreatment that’s actually just everyday business for a publisher.

It’s hard not to notice that both incidents took place during Pride Month. It’s a time when visibility, identity, and allyship are at their highest, and when marketing campaigns around queer authors are most active. Is it coincidence? Maybe.

But it’s also hard to ignore the pattern of emotional storytelling, vague injustices, and a viral payoff.

Next Day Decision

The very next day, Paul Castle returned with a new TikTok promoting a follower’s suggestion that he should publish other children’s book authors under his imprint. Because once he represents ten titles, he might be eligible to distribute through Ingram and gain traction. Many felt it a premeditated choice by Castle. Either way, my gut reaction to this news was… Red FLAG!

Eager debut authors might perceive this as a fast track to becoming published— aligned with the allure of being “on the ground floor” with a queer, disabled author they admire. But what happens when reality hits? Unlike authors protected by agents or traditional presses, these newcomers would have no legal advocate watching for fair contracts or ethical publishing terms. They’d be financially, artistically, and reputationally vulnerable.

Moreover, consider how risky indie presses really are. Even well-funded imprints have collapse rates of 20–30% within a few years. Building a press on emotion and social momentum (not infrastructure) can be disastrous for trusting writers. Not to mention that if you believe all of Castle’s stories, thus far, he has failed repeatedly to get his own books into bookstores. Why would he be more successful with yours?

If you’re moved to support queer, disabled, BIPOC, and otherwise marginalized authors, please do! Just make sure your support is going where it matters. Here are a few trusted organizations and resources doing the work:

PEN America – Advocates for free expression, fights book bans, and uplifts voices that are often silenced.

We Need Diverse Books – A nonprofit dedicated to putting more diverse books into schools, libraries, and the publishing pipeline.

Disability in Publishing – Supports disabled publishing professionals and pushes for accessibility and representation.

Lambda Literary – Champions LGBTQ+ authors through awards, fellowships, and writing programs.

Instead of falling for viral pity marketing, consider donating, amplifying, or buying books through these channels where it will make a real difference.

This couple has been complicated for me for awhile. When I saw the story the first time, it threw a huge red flag because there had already been a similar story about his dog not being allowed in a restaurant that felt incomplete. People need to understand how algorithms work, these emotional stories are click bate encouraging the creator to craft a story that is possibly a little on the wrong side of true all for the likes, comments, and shares. They make money from all of that through TikTok then for their book sales. It's a business, not necessarily a fact based story.